|

| Juan Luis Avilés Moreno at the Common Ground Country Fair with (left to right) interpreters Jan Morrill and Christa Little-Siebold and (right) MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee member Karen Volckhausen. English photo |

|

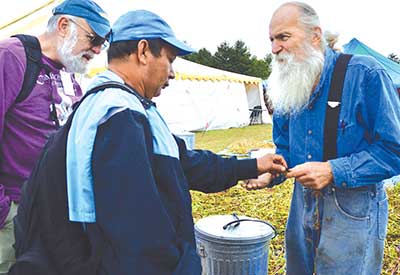

| Avilés Moreno (center) talks with Will Bonsall about grain processing at the Fair. Jim Torbert, interpreter and MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee member, is on the left. English photo |

|

| Areas of sugar cane cultivation in El Salvador |

|

| Sugar cane is burned before harvest to remove outer leaves from the stalks, resulting in air pollution, soil degradation and illness among farmworkers and local citizens. Photo courtesy of Juan Luis Avilés Moreno |

By the MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee

Organic farmer Juan Luis Avilés Moreno works with Salvadoran nonprofits. He has been a grassroots agricultural technician with CORDES (Foundation for Cooperation and Community Development in El Salvador) since 1993. He is a delegate of CORDES and CRIPDES (Association for the Development of El Salvador), as well as a leader of APROINORES (Association of Agroindustrial Producers of El Salvador), which consists of 15 growers of certified organic cashews, cacao and mangos.

Avilés Moreno is also a former board member of UK-based Liberation Foods, which markets produce from small-scale nut growers from around the world. He, his wife and three sons grow cashews and cacao trees on their land. Their crops are certified through BCS Germany and FLO Fair Trade. He has shared his expertise during trips to Europe, South America and India.

Also, Avilés Moreno is an agricultural technician with MOPAO (Grassroots Movement of Organic Agriculture, or Movimiento Popular de Agricultura Orgánica), which promotes organic farming first as a means of food security for Salvadorans and second as a way to participate in international organic markets in the United States, France, England, Germany and Canada. He came to the 2018 Common Ground Country Fair as a guest of the MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee to speak about “the bitter side of sugar cane.”

Avilés Moreno listed problems associated with conventional sugar cane cultivation in El Salvador:

- Sale or rent of land leading to loss of family assets and migration

- Aerial spraying, which prohibits sowing other crops and sometimes contaminates organic crops, leading to loss of organic certification on about 500 acres. Applied pesticides often fall on the backs of field workers. After working for 10 years in the sugar cane fields, people often die, said Avilés Moreno.

- Burning of cane tops; fires can spread to other fields, they release CO2 to the atmosphere and they kill soil microorganisms

- Monoculture, which leads to loss of biodiversity, to soil degradation and erosion, and to deforestation

- Expansion by sugar cane companies into areas of protected forest

- Use of scarce water resources to irrigate sugar cane

- Intrusion of salt water in arable areas when ground water is extracted for irrigation

- Contamination of ground water and watersheds with agricultural chemicals that have been banned worldwide but are still being used in El Salvador

- Increasing incidence of chronic kidney disease among cane workers

Coastal areas previously used as cotton plantations have been switched to sugar cane production, using the same dangerous production techniques. In Tecoluca, 85 percent of the best land is being used for cane production.

Some Salvadoran universities give scholarships sponsored by Monsanto and other large transnational corporations to university students, said Avilés Moreno. The students test new chemicals on experimental agricultural plots. They are asked to pay for an insurance policy on the crop so that if everything dies, the money is recuperated.

MOPAO, made up of 17 smaller organizations, started in 2007 to respond to pollution in the municipality of Tecoluca, where about 6,200 acres of sugar cane grow. MOPAO advocates stopping the use of prohibited agrochemicals, the indiscriminate use of El Salvador’s limited water supply, and field burning. It also works with schools to educate children to care for natural resources and the environment, and with senior citizen members of the Bajo Lempa Rural Association of Older Adults. It helps construct greenhouses and create community gardens, for example.

MOPAO is keeping an eye on development, as well. “Our region has not been developed yet,” said Avilés Moreno. “We produce the majority of our cashews near the mouth of the Rio Lempa, the largest river in Central America, which crosses three countries. But at the mouth of the river is a beautiful island, and Chinese and Taiwanese investors have shown interest in developing a hotel there. We still have our mangroves, our coastal areas that aren’t populated by hotels, but we’re afraid that in the future there will be more development for tourism.”

One of the biggest challenges the country faces, continued Avilés Moreno, is an effort to privatize water. Currently each community has its own water source and administers water based on the consumption of the household or the family. If those are turned over to private companies, the companies will charge whatever is necessary to make a profit. He noted that a group of private businesses producing Coca Cola, bottled water and beer currently has an agreement with the Salvadoran government so that they don’t have to pay taxes on the water they use, but they also want to privatize the water in order to make more profit.

Jim Torbert, a member of the MOFGA-El Salvador Sistering Committee and of the MOFGA board, pointed out that these are multinational corporations that are buying water rights everywhere, including in Maine.

Avilés Moreno said, “That’s been the problem for a long time. The people who are on top want more, at the expense of the people on the bottom. That’s why we fought our civil war for so many years. Right now the current government gives shoes, uniforms and notebooks to children who are going to school, but the private industries say that’s a waste of money.”

He said he has received death threats from people sent by owners of the sugar cane companies. “We look to the activists who were killed in the anti-mining campaign, and we know we’re taking a risk. There’s a song that says you have to live to die. I accept that I will die at some time, and this is a risk that I am willing to take.”

He continued, “We have a history of 14 families ruling the country, and our fathers and families worked as indentured servants in coffee, cotton, indigo, and as fishermen. We had a difficult armed struggle with many deaths to fight for the little pieces of land that we have. We have to protect what we have. Archbishop Romero and 70,000 civilians were killed during the civil war so that we could each have a tiny piece of land. We have to take care of that.”

Avilés Moreno thanked MOFGA and those (including Congresswoman Chellie Pingree) who helped him get a visa to visit the United States – something that’s very difficult for someone from Central America now. He said he was impressed with the Common Ground Country Fair, noting that the cashew fair held in his area is about one-fifth of the size of Common Ground. While in Maine he also spoke to students in Professor Doug Fox’s class at Unity College, and he toured farms from Cumberland to Hancock County.