|

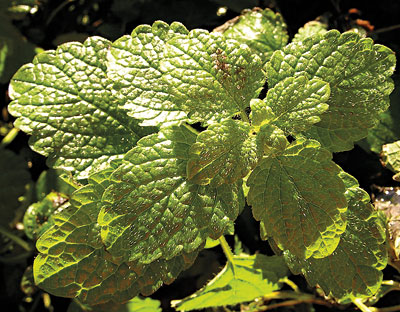

| Oats. English photo |

By Joyce White

Plants known as herbs have been a part of healing the body, mind and spirit for most of known human history. Cultures have differed, stresses have differed, but the use of plants for healing as well as for food has remained constant through time.

The brain, it was previously thought and taught, is the command center of human thought and activity, but new research places the heart – the feeling, emotional aspect of humans – in that position. Herbalist David Hoffman in “Herbs for Healthy Aging” uses the term mind/body connection (as have many other writers) in discussing herbs called adaptogens, but he also includes the spiritual aspect in discussing healing.

Adaptogens help the human body “adapt to stress, support normal metabolic processes, and restore balance. They increase the body’s resistance to physical, biological, emotional and environmental stressors and promote normal physiologic function,” state herbalists David Winston and Steven Maines in their book, “Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina, and Stress Relief.”

Adaptogens are uniquely able to do so, says Dwight McKee, M.D., in “Adaptogens and the Neuroendocrine System,” because “they influence the neuroendocrine system where they improve the utilization of oxygen, proteins, fats and sugars and support the protective defense system of the body.”

Adaptogens themselves aren’t new. They have been called by other names in the past, such as rejuvenating herbs, qi tonics and restoratives. Russian scientists coined the newer term in the 1960s. Many of these adaptogens are especially helpful in mediating feelings of emotional discomfort or mental dysfunction and are termed nervines.

What is especially interesting in using herbs is the many different actions that each plant displays, each comprising a variety of chemical constituents. Thus, each herb can influence several aspects of human physiology and emotion.

Winston and Maines state that if we can improve our mental condition, we can improve overall health. Recent studies indicate what most of us have observed in our own lives, i.e., that mental or emotional stress triggers changes in the immune system and that people suffering from depression have higher rates of heart disease and cancer.

In addition to the lifestyle and dietary changes that Winston and Maines believe necessary for most people suffering from stress-related discomfort, they suggest that adaptogens can be helpful – especially the nervines, those herbs that calm and relax while also nourishing the nervous system and helping to restore emotional balance.

Fresh Milky Oat

Winston and Maines describe fresh milky oat (Avena sativa – the common oat plant) as a superb food for the nervous system. “It is a slow-acting tonic remedy that calms shattered nerves, relieves emotional instability, reduces symptoms of drug withdrawal and helps restore a sense of peace and tranquility.” They term it a trophorestorative herb, meaning a food for a specific tissue.

The immature oat seed, the part used, needs to be harvested during the one week in the growing season when the immature seed is filled with a white, milky substance. Because of changes in its chemistry, if it is harvested quickly at just the right time and made into a fresh tincture (an alcohol extract of the medicinal properties of the plant), it becomes, in their opinion, the best food herb known for nourishing the nervous system. It has been used for more than 150 years, first noted to have been used by the Eclectic physicians. (Oatmeal and oat straw both come from the same plant and are useful as food and medicine, but they don’t have the same effect as fresh milky oat.)

Rudolph Ballantine, M.D., in “Radical Healing,” describes the Eclectic Medical Institute, originating in 1845, as a movement founded in folk medicine. It “became a major force in blending the herbal medicine of European origin with the herbal lore of the many Native American tribes,” he says. By the 1880s the Eclectics had trained more than 10,000 physicians and acquired unprecedented prestige and influence lasting well into the 20th century.

Ballantine says that an official pharmacopoeia of Eclectic preparations, including fresh milky oat, was first published in 1854 and went through 19 editions. By the turn of the century, however, the rising pharmaceutical industry was making significant inroads into the medical field, “bringing a new philosophy of ‘patent’ medicines that was financially lucrative. Because the largely herbal medicines of the Eclectics did not lend themselves to economic exploitation of this sort, the competitors soon outstripped them in power and influence.” Also, it was easier for physicians to prescribe the new patent medicines, and with the advent of sulfa drugs – the first antibiotics – in the 1930s, the ranks of the Eclectics thinned drastically. The last of the Eclectic medical schools closed in 1939. As the schools closed, significant books and papers went to Lloyd’s Library in Cincinnati.

|

| Astragalus membranaceus. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astragalus_propinquus#/media/File:Astragalus_membranaceus.jpg |

Astragalus

Winston and Maines describe astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus) as native to China and an integral part of Chinese medicine for at least 2,000 years. It is called Huang qi in that system. The yellowish root is used. It is found in markets as dried slices that resemble tongue depressors for use in immune-strengthening soups. It can be purchased in capsules of the powdered root or as alcohol tinctures. The perennial grows in sandy, well-drained soil and doesn’t like mulch or deep cultivation, says Stephen Buhner in “Herbal Antibiotics.” Although most sources rate astragalus as a zone 6 plant, Deb Soule of Avena Botanicals in Rockport, Maine, has an excellent video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XUoqASSATA showing it growing as a perennial in Avena’s zone 5 herb garden. This MOFGA-certified organic (and Demeter-certified biodynamic) producer also shows how to cook astragalus roots and discusses their medicinal properties.

Maines and Winston describe astragalus as containing immune-stimulating polysaccharides as well as other constituents that contribute to its antibacterial, antioxidant, heart and immune tonic properties. In the Chinese system, astragalus strengthens the qi, the life force energy of the body. One result of that action is to reduce excessive sweating, including that of menopause.

Astragalus enhances immune function, helping prevent colds, flu, bronchitis, mononucleosis and pneumonia. “It also helps prevent immunosuppression caused by chemotherapy and has tumor-inhibiting activity,” say Maines and Winston, adding that it has been used to improve cardiac blood flow and that regular use has been shown to prevent kidney and liver damage caused by medication and viruses.

Stephen Buhner in “Herbal Antibiotics” states that astragalus “was not used in Western botanic practice until the tremendous East/West herbal blending that began during the 1960s. It is now one of the primary immune tonic herbs in the Western pharmacopeia.” In “Healing Lyme,” Buhner recommends using astragalus regularly to prevent Lyme disease, but he also warns that anyone suffering from late-stage Lyme disease should avoid astragalus, “because it can exacerbate autoimmune responses in that particular disease.”

Hoffman, in “Herbs for Healthy Aging,” adds that the polysaccharides in astragalus intensify the activity of white blood cells, stimulate pituitary-adrenal cortical activity and restore depleted red blood cell formation in bone marrow. Astragalus also stimulates the body’s natural production of interferon.

|

| Hawthorn. English photo |

|

| Lemon balm. English photo |

Hawthorn

Introduced into North America, hawthorn (Crataegus oxycanthoides) now thrives along roadsides and fields from Canada to North Carolina. White or pink flowers arrive in late spring, producing red, oval berries in late summer. Berries, flowers and leaves are used in medicine, which Winston and Maines describe as a trophorestorative for the heart and circulatory system. Hawthorn is well known as a treatment for cardiovascular conditions – it works well to restore normal heart rate and rhythm in cases of arrhythmia, strengthens the heart, treats or prevents atherosclerosis – but is less well known for its nervine actions. Winston and Maines connect its use as a nervine with the idea from Chinese medicine that the heart stores life force energy and that disturbed heart energy symptoms include anxiety, insomnia, bad dreams, heart palpitations and irritability.

Candace Pert, author of “Molecules of Emotion,” confirms the heart/emotion connection. Her research demonstrates that the heart is not just an organ to pump blood but also has receptors for a wide variety of hormones and neuropeptides that affect the emotions.

Richard Gerber, M.D., in “Vibrational Medicine for the 21st Century,” comments, “New research is pointing to the influence of the ‘heart/brain connection’ upon how we think and feel and experience stress.” Our emotions strongly influence the activity of the heart; anger and hostility are generally recognized as possible contributing factors in heart disease.

Lemon Balm

Of the mint family, lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) is native to Europe and has become a naturalized perennial in much of the United States. Dried or fresh leaves of this lemon-scented herb are used as medicine and tea. Herbalist David Hoffman, in “Herbs for Healthy Aging,” describes its uses as carminative (gas relieving), nervine, antispasmodic and antidepressant. It is indicated primarily, he says, when there’s “dyspepsia associated with anxiety or depression, as the gently sedative oils relieve tension and stress reactions.” The volatile oil appears to act on the interface between the digestive tract and the nervous system. Some herbalists term it a restorative to the nervous system.

Winston and Maines mention its use as a nourishing tea to be drunk simply for pleasure or for its mood elevating and nervine effect. Studies on humans, they say, indicate that it can “enhance cognitive function, improve mood and remove some of the symptoms of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, especially irritability and forgetfulness.”

Gathering lemon balm for tea or tincture before it flowers will assure that it retains its mild, lemony flavor and fragrance. Gathered later, it may have a slightly bitter taste for tea. Lemon balm leaves can be harvested and dried for later use as tea or medicinal tincture.

|

| St. John’s wort. English photo |

St. John’s Wort

St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), a perennial herb bearing yellow flowers, now growing wild in eastern Canada and the United States, has become known as the “depression herb.” That’s unfortunate, say Winston and Maines, because although it is useful for addressing some types of depression, it has a much broader range of uses. Each herb has a range of uses, actions and specific qualities. Real herbal medicine, they say, is more than using an herb to replace a pharmaceutical medication. Instead it “uses diet, herbs, and lifestyle changes to prevent illness, relieve symptoms, and enhance normal physiological function.”

St. John’s wort has been used since the time of the ancient Greeks to treat conditions of the nervous system, including nerve pain and nerve damage. Taken as a tincture, it is effective for treating the pain of neuralgias, carpal tunnel syndrome, head trauma, peripheral nerve pain and phantom limb pain. Used as an oil – called hypericum oil – it is helpful for treating burns, bruises, insect bites, muscle tears and shingles.

This is a small sample of the many adaptogen herbs available. I chose them because they are readily available, made from Maine-grown herbs, through Avena Botanicals in Rockport. “Healing begins in the garden,” succinctly states Avena’s philosophy on its catalog cover. It lists several more adaptogens, and Maines and Winston describe even more, many of them Chinese herbs with which I am not familiar. Among those that will be familiar to many are ginseng, black cohosh, ashwaganda, blue vervain, catnip, holy basil, licorice and reishi mushrooms.

References

Ballantine, Rudolph, M.D., “Radical Healing,” Harmony Books, New York, N.Y., 1999

Buhner, Stephen Harrod, “Healing Lyme: Natural Healing and Prevention of Lyme Borreliosis and Its Coinfections,” Raven Press, Randolph, Vermont, 2005

Buhner, Stephen Harrod, “Herbal Antibiotics,” Storey Publishing, North Adams, Massachusetts, 2012

Gerber, Richard, M.D., “Vibrational Medicine for the 21st Century,” Harper Collins, New York, N.Y., 2000

Hoffman, David, “Herbs for Healthy Aging,” Healing Arts Press, Rochester, Vermont, 2014

Winston, David and Steven Maines, “Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina and Stress Relief,” Healing Arts Press, Rochester, Vermont, 2007

About the author: Joyce continues to learn about, grow and gather medicinal plants in garden and fields around her home in Stoneham, Maine, with the aim of becoming more self-sufficient in healthy aging.

This article is for information only; please consult a health care practitioner to learn about possible side-effects and if you have a serious medical problem.

Top