Pest: Aphids

Aphids are perhaps the soft-bodied insect pest most well-known to both farmers and gardeners. There are many different species of aphids, but green peach (Myzus persicae), melon (Aphis gossypii), potato (Macrosiphum euphorbiae), and foxglove (Aulacorthum solani) are the most common aphid species of concern in the Northeast.

Some aphid species may have greater affinities for specific crops than others, but these common aphids are generalists that happily infest many different crops. Damage potential from aphids is usually greatest in warm, protected growing spaces like tunnels/greenhouses or under row cover.

Aphids feed by stabbing hollow, sharply pointed mouthparts into plants to suck out their juices. While this direct removal of nutrients can have a negative impact on growth of infested plants — particularly when colony populations have exploded — a greater damage can come from the plant viruses that aphids can transmit. They also cause distorted growth where they’ve been feeding and cosmetic concerns from their waste.

Aphids extract more sugary plant juices than they can actually use and excrete a waste that is still very sugary, referred to as “honeydew.” The sticky and shiny honeydew falls to foliage and other surfaces below the aphids and can be unsightly enough on its own, but it also feeds sooty mold, which leaves plants looking dirty and can grow thick enough to reduce their photosynthetic potential. Aphids also molt their exoskeletons multiple times as they grow rapidly, and these discarded white skin casts are sometimes the most visible sign of their infestation — and may be concerning to customers of seedlings/nursery crops.

Pest/disease identification and lifecycle:

While aphids are often a shade of green, their coloration can vary quite a lot — even within the same species — and they are sometimes shades of orange, pink, red, or black. Some aphid species are larger than others, ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 millimeters (1/16 to 1/8 inch) in length, but they also vary in size by age.

In many situations it is not important to identify exactly which species of aphid(s) are infesting your crops, but it can be the critical difference between failure and success when managing them with biological control options like parasitoid wasps. In that case, it’s necessary to determine if you have the smaller species (green peach or melon aphids) or the typically larger species (potato or foxglove aphids). The two most commonly purchased biocontrol species of parasitoid wasps have a preference for larger or smaller aphids.

While I recommend that every grower at least have a hand lens to help them make their own identifications while scouting crops, aphid species are difficult to tell apart and oftentimes the fastest or best way to know which species you have is to take a very detailed photo or three, and send them to an expert for identification assistance (e.g., extension or certain biocontrol supply companies). There are many affordable clip-on lenses to help you take magnified photos with a smartphone, and even some tiny stick-on lenses that can be reused many times if well cared for (Blips is a brand that I’m familiar with).

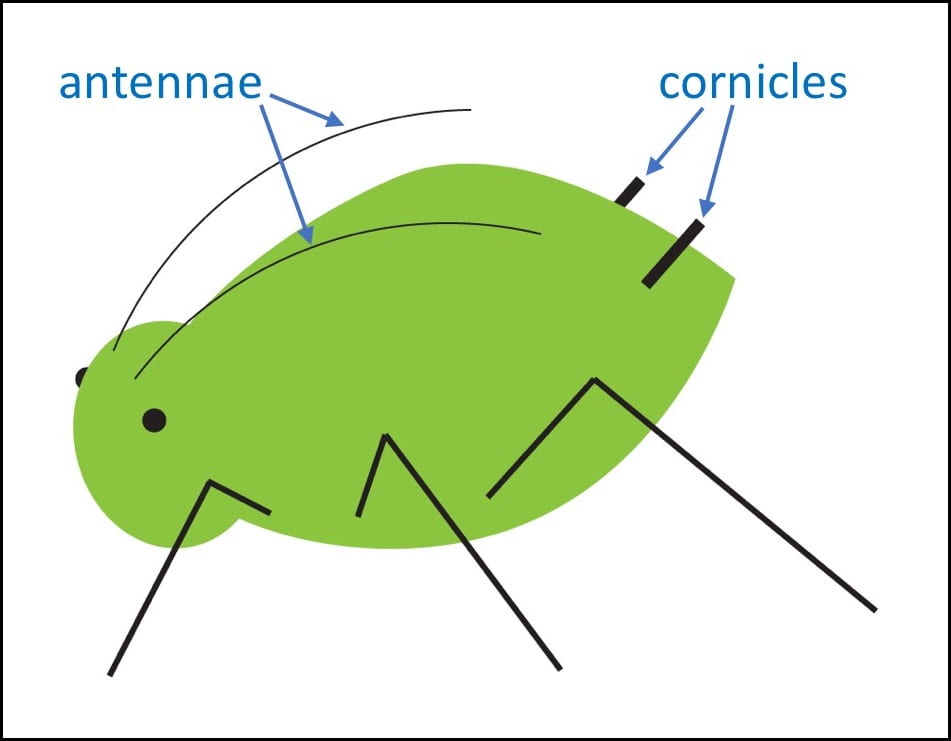

Some of the best identifying features of aphid species include their overall size, the positioning of the “tubercles” that support their antennae, and the size of their “cornicles” (two tubes protruding from their rear). Of the species listed here, all but the melon aphid typically have the appearance of an indentation on the front of their head, in between their antennae. The most memorable description of which I’ve heard is that it looks like they ran face first into a tiny two-by-four. Melon aphids will also always have dark cornicles, regardless of the color of their body. Green peach aphids’ cornicles will mostly match the color of their body but have black tips at their ends. Foxglove aphids may also have black cornicle tips but with a distinguishing feature of distinctive dark spots on their bodies at the base of their cornicles. Foxglove aphids also tend to have darker coloration at their leg joints and at the many joints of their particularly long antennae. Potato aphids’ bodies may look a bit more segmented than the other species and have a dark stripe running down the middle of their backs.

Management options:

Scouting:

Scouting is ideally performed early and often enough in greenhouse settings to catch aphid infestations before they cause more apparent damage. It can be more difficult to catch infestations early in outdoor settings, but they also tend to be less consequential to overall production, and are frequently kept in check by wild predator and parasitoid populations. Scouting is most important when transitioning new plants to protected growing situations where aphids can multiply rapidly and be protected from predators and parasitoids, e.g., when quarantining incoming plant material like nursery starts before bringing them into a greenhouse; when planting transplants out to a bed that will be covered with row cover; or when checking prior crops and weeds in a tunnel that will be turned over to a new crop — both in the fall before winter crops and in the spring before seedling production or summer crops.

Aphids are usually found on stems, buds, and the underside of leaves on tender new growth, where they can feed more easily. Magnification is essential when you desire to identify aphids by species (see the sections on identification and biocontrol options). Careful investigation is important to catch and quantify early infestations. However, it may be easiest and most efficient to first scan larger areas of plants for yellowing or distorted upper leaves, and/or lower leaves with a shiny look (from honeydew), and/or a collection of white skin casts. These cast skins are often an easily noticed early sign of an infestation.

Yellow sticky cards can be used to monitor aphid presence but should not be expected to provide an infestation warning early enough to manage aphids most effectively. Remember that colonies will typically only begin producing winged adults after they have begun to be overcrowded. (However, yellow sticky traps can be beneficial in letting you know that you have a colony nearby producing winged adults, if you didn’t know that already!)

While scouting for aphids, you should also be looking for signs, or the presence, of predators and parasitoids. Some insecticides for aphid control could also be damaging to their natural enemies and should be avoided if aphid populations aren’t too high and predator and parasitoid populations are present. Predatory larvae of several species (green lacewings, lady beetles, Aphidoletes midges) can often be fairly easily identified among aphids when present and are worth learning in addition to their better known adult forms. Presence of parasitoid wasps can be verified by finding aphid “mummies” — the typically brown, rounded body of an aphid that a parasitoid wasp has laid an egg into, sometimes also with a circular exit hole showing where the newly pupated wasp offspring has emerged. Ants can also be an indicator of an aphid infestation, particularly in garden settings: They will often “farm” aphids, moving them around to other plants and protecting them in exchange for being able to feed on the honeydew they produce.

Cultural:

In all situations, good sanitation will help to reduce chances for aphids to jump to your next crop. This includes removing/burying crop debris that may be harboring overwintering eggs, and controlling weeds that may be hosting aphid colonies that could jump to your crop — this is particularly important in a tunnel that’s to be planted to winter greens, or when a winter greens tunnel is to be terminated and turned over to spring or summer production. A two-week “dead period” with no plants may be helpful to starve out any existing aphid colonies, particularly in the late winter when tunnels are mostly closed up and winged adult aphids are less likely to find their way in from elsewhere.

Because of their frequency as prey to many different species, aphids in outdoor settings are essentially the potato chip of the insect world, and their populations are typically kept in check by wild predators and parasitoids. Management considerations are focused on fostering and maintaining a diversity of habitat to support these beneficial insects, and sometimes knocking back an aphid infestation temporarily, while waiting for wild predators and parasitoids to build up enough numbers to keep populations in check. Keep in mind that aphid reproduction can be much faster than that of predators and parasitoids, and this difference is typically most noticeable earlier in the season, especially if aphids have had a chance to multiply in a warmer protected space. A powerful blast of water is frequently sufficient to physically remove enough aphids from plants to set their population back temporarily. Doing this once or twice in June may be the only intervention required in a small garden, or even on a farm if a diversity of beneficial insects are present and supported. Having a diversity of plants helps to provide beneficial insect habitat and maximize bloom period for an extended supply of pollen and nectar. Examples include dedicated habitat strips, interplanting crops with species like alyssum, and something as simple as letting cilantro and dill go to flower after primary leaf harvest is done.

Avoid overfertilization with nitrogen, as it can result in rapid growth of succulent plant tissue, which tends to be weaker and more easily fed upon. Aphids have greater growth and reproductive success rates on plants receiving higher levels of nitrogen.

Biocontrol Options:

In protected growing environments like high tunnels and heated greenhouses, purchased biocontrol species can be very effective. In outdoor field settings, it typically does not make financial sense to buy biocontrol species, except possibly if releasing within a row-covered planting. This is primarily because of the high mobility of the adult forms of these species and the frequently pre-existing but often undervalued presence of wild predatory and parasitoid species. The difference in value of plants per square foot of growing area in the field versus under cover is also a key factor.

Parasitoid wasps are among the most effective during warmer months and when an area is heated, provided that they are introduced preventatively or at the very first sign of aphids. Many predatory species will also assist in reducing aphid populations but may not have the same control potential as parasitoids. In all cases, the biocontrol species’ ideal temperature and daylength conditions must be considered, as some will not be effective in winter months.

For best results with parasitoid wasps, aphid species should be identified. The wasp species Aphelinus abdominalis and Aphidius ervi will attack and lay eggs into larger potato and foxglove aphids, while Aphidius colemani will attack and lay eggs into the smaller green peach and melon aphids (see the identification section). An alternative approach to identifying the aphid species present, or to deal with the presence of both a larger and a smaller species, is to order a blend of parasitoid wasp species and leave it to them to decide which aphids they’ll be hunting down.

Because parasitoid species take a longer time to build up a population capable of controlling an aphid outbreak, one method that can make the purchase of A. colemani most effective and worthwhile is the use of a “banker plant” system, typically oats, grown in successions to maintain a population of cereal aphids (which do not feed on most common greenhouse crops). The banker plants are grown within some sort of insect exclusion, which is sequentially removed to provide hosts for your population of parasitoid wasps to lay eggs in, keeping them reproducing and providing a continued presence.

The most common predatory species can often be purchased from commercial sources fairly easily: green lacewing (Chrysoperla carnea), convergent lady beetle (Hippodamia convergens), and Aphidoletes midges (Aphidoletes aphidimyza). While Aphidoletes midges have evolved for their larvae to specifically prey on aphids, and could potentially provide a similar level of control to parasitoid wasps, green lacewings and lady beetles are both generalists and may also feed on thrips and whitefly. Lady beetles may also feed on scale and mealybugs as well. In all three species, their larvae do the most feeding on aphids, though adult lady beetles will also feed on them.

Some important considerations when shopping for predatory species include the time of year (in regards to both temperature and daylength); how enclosed they will be (are tunnel sides open?); and will they find enough food to keep going (both the aphids, which their larvae require, and flowers, which the adults may require for pollen and nectar). While there may be other lab-reared lady beetle species available at times, the most common species available for sale is the convergent lady beetle, which are frequently wild collected, posing a potential ethical concern as well as a chance of them arriving to you infested with their own wild parasitoid or disease species.

In general, lady beetles are the only species that will remain active in the late fall and winter months, but they are also quick to leave if they do not find abundant food and are able to escape. As winter transitions to spring, and tunnels and greenhouses are warmer, Aphidius parasitoid wasp species have the greatest potential efficacy if brought in prior to aphid colonies blowing up in population. This period of efficacy can be extended with repeated releases or the use of a banker plant system. In protected growing spaces in the summer months, Aphidoletes midges may be the best biocontrol response to an aphid flare-up, but green lacewings can help to keep low populations in check and will also feed on other common pests.

Organic pesticides (as a last resort):

In all cases, pesticide use should be considered carefully in regards to potential interference with predator and parasitoid species, whether wild or purchased. Oftentimes the best use case for pesticides against aphids is as the first punch in a one-two punch approach: first knocking back a population that may have been discovered too late for truly effective management with biocontrol species alone. Check with biocontrol suppliers regarding pesticide compatibility with the species you are purchasing, particularly if you have already deployed some.

Being soft-bodied, aphids are more vulnerable to some lower-risk pesticide options than other pests, and it may be best to start with a soap product like M-Pede or an oil product like stylet oil.

Other partially effective options — but potentially more consequential to beneficial insects — include pyrethrin (e.g., PyGanic) and azadirachtin (neem-based products, e.g., Aza-Direct, AzaGuard, etc.). These are probably best reserved for severe infestations, and scheduled a day or two prior to arrival of biocontrol species, to allow for their breakdown. Without following up with biocontrol species, these materials may make the situation worse, killing slower-to-rebound beneficial insects, while only temporarily hindering the rapidly reproducing aphids.

Aphids are also vulnerable to bio-insecticides, like the Beauveria bassiana entomopathogenic fungi products, but those can also infect beneficial insect species. The best use case for these products is likely in fall and winter high tunnel production when most biocontrol insect species are not active, and when days are short and humidity levels tend to be higher, giving the fungus a better chance to successfully infect the pests before drying out. Good spray contact with the pests is needed for best efficacy, as well as repeated applications. However, thorough coverage may be difficult to achieve in densely grown winter greens.

Please note: This information is for educational purposes. Any reference to commercial products, trade, or brand names is for information only, and no endorsement or approval is intended. Pesticide registration status, approval for use in organic production and other aspects of labeling may change after the date of this writing. It is always best practice to check on a pesticide’s registration status with your state’s board of pesticide control, and for certified organic commercial producers to update their certification specialist if they are planning to use a material that is not already listed on their organic system plan. The use of any pesticide material, even those approved for use in organic production, carries risk — be sure to read and follow all label instructions. The label is the law. Pesticides labeled for home garden use are often not allowed for use in commercial production unless stated as such on the label.

Authors

Written by Caleb Goossen